Mangrove ecosystems: Vital coastal guardians for a sustainable future

Indonesia is home to 21% of global mangrove ecosystems that provide livelihoods and food sources for 120 million people. Under the threats of land use and land cover change, these ecosystems have become increasingly scarce, causing detrimental impacts to climate resilience and local communities.

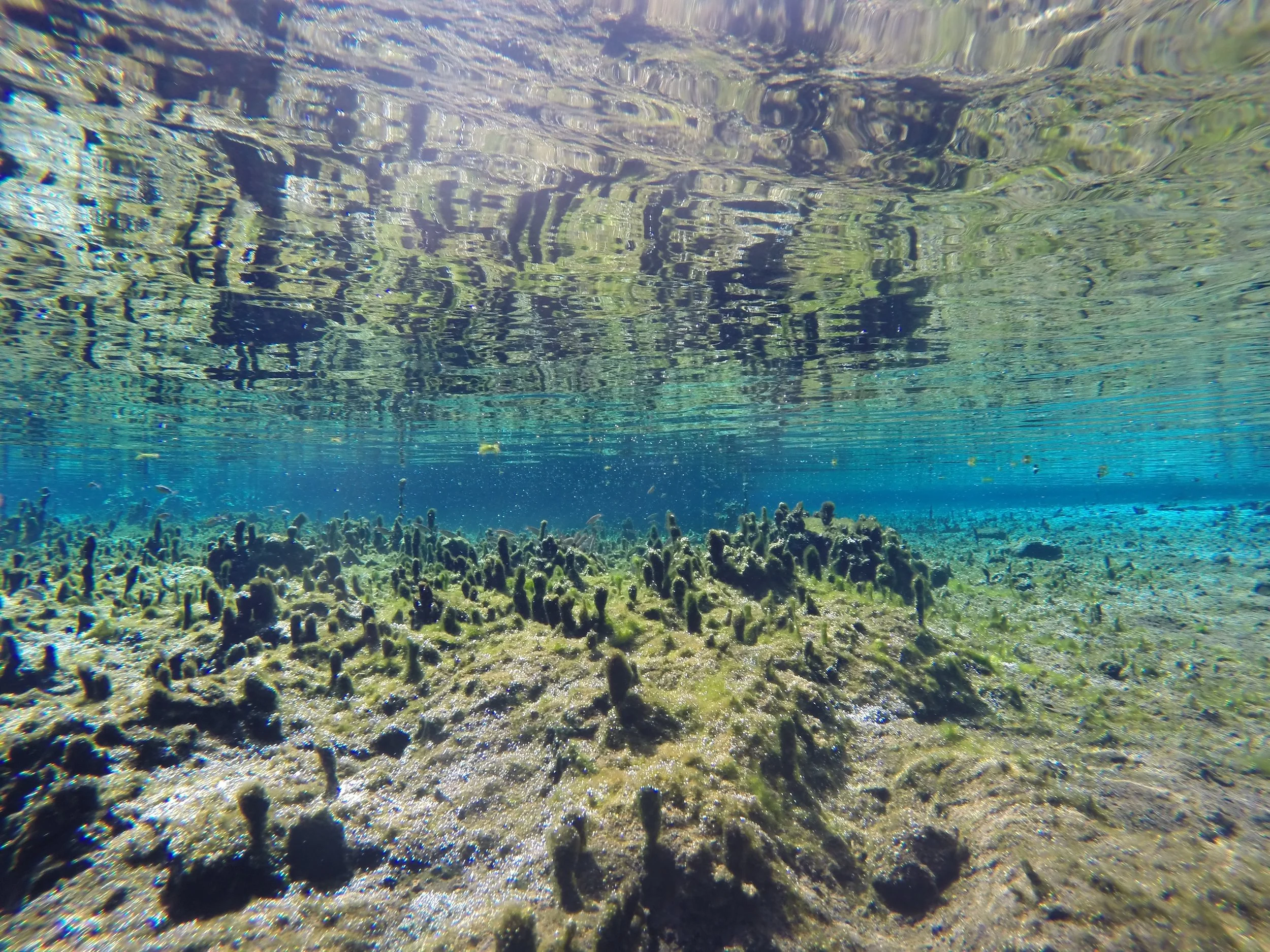

Photo by Carin Noerhadi

Mangrove ecosystems are unique coastal environments found in tropical and subtropical regions, characterized by salt-tolerant trees and shrubs that grow in intertidal zones along coastlines, estuaries, and riverbanks.

Globally, mangroves cover an estimated 136,000 km² of tropical and subtropical shorelines. Over a third of the world’s mangroves are found in Southeast Asia, with Indonesia's mangroves spanning 30,000 km² of coastline or 21% of the global total. Mangroves can remove and store up to four times more carbon dioxide per hectare than terrestrial forests, making them a crucial component in combating climate change.

Mangroves play a critical role in coastal protection, biodiversity conservation, and carbon sequestration. They provide habitats for various species, including fish, birds, and invertebrates, and serve as nurseries for many marine organisms. For people living around mangrove ecosystems, these environments are a vital source of food and livelihoods, from fishing to forestry products. In return, local communities take on the role of mangrove guardians, protecting and preserving these vital ecosystems.

Mangroves, local communities, and food systems

The relationship between mangrove ecosystems and their inhabitants is multifaceted and deeply interdependent. This connection spans ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions, highlighting the importance of mangroves in the daily lives and overall well-being of local communities.

For instance, in Ambon Dalam Bay, Moluccas, a group of Indigenous Peoples residing in Kampung Passo, Nania, Negeri Lama, and Waiheru close to the mangrove forests relies heavily on the ecosystem and is thus significant for ecosystem conservation. They regard mangroves as crucial for protecting both the sea and mainland, reducing damage from terrestrial sedimentation and pollution, and acting as a natural barrier against abrasion, seawater intrusion, strong winds, storms, and tsunamis.

Their relationship with the adjacent mangroves is symbiotic: While they depend on the ecosystems for their livelihoods, the ecosystems depend on them for conservation.

For them, mangroves are 'the tree of life’ as they provide habitat for primary food sources, such as fish, shrimp, and snails, as well as their income and sustenance.

To ensure a consistent supply of these resources, they engage in voluntary conservation efforts, preserving the mangroves that support their livelihoods. The harvested fish, shrimp, and snails are either sold or consumed by families, contributing significantly to their economic well-being. Although these conservation efforts do not directly translate into immediate economic compensation, they are crucial for the long-term sustainability of these resources.

Another example is found in the all-women community of Youtefa Bay, Papua, who finds a sense of freedom in the mangrove forests of what is known as the ‘Women Forest’ (Hutan Perempuan).

Hutan Perempuan represents a sacred mangrove forest nurtured by women with traditional knowledge passed down through generations. It is an integral part of their food culture, where community members gather and forage for food while men fish in the sea. Dedicated to women only, this mangrove forest fines men entering the area with beads valued between Rp300,000 and Rp1,000,000.

Beyond ecological, economic, social, and cultural dimensions, mangrove ecosystems naturally provide good nutritional sources for the adjacent populations.

A cross-sectional spatial analysis revealed that families living near high-density mangroves (0-5 km from mangrove forest) consumed 28% more fresh fish and other aquatic animals than those in medium-density mangrove areas (>10 km from mangrove forest) or far from mangroves. This is good news for Indonesia, as marine fish consumption is linked to lower health risks, better cognitive scores, and reduced likelihood of stunting.

However, our mangrove ecosystems are in grave danger.

Major mangrove threats

The total mangrove loss from 1980 to 2005 in Indonesia covers an estimated area of 52,000 hectares per year (30% of total mangroves in the country). The main drivers include land conversion to shrimp farming, rice agriculture, oil palm plantations, and wood harvesting, as well as natural disasters and climate change.

Some communities are experiencing these threats firsthand.

The increased weather volatility and frequency of extreme weather events have made fishing and other livelihood activities more difficult, often preventing local communities from going out to fish and negatively impacting food and nutrition security.

Villagers in Batu Ampar, West Kalimantan, are among the communities that utilize mangroves for employment and food procurement. In recent years, they reported that land conversion for the pond and palm plantation industry is altering fishing infrastructure and slowly eliminating traditional fishing practices.

Reflecting on the challenges posed by this conversion, interviewed fishermen expressed their concerns about the negative impacts of industry on their mangrove-based livelihoods and the health of the mangrove ecosystems due to pesticide runoff and deforestation.

As mentioned before, the mangrove ecosystem provides numerous benefits, such as protection against storms and wave actions. When mangroves are cut down for palm plantations, aquaculture, and other businesses, it disrupts these essential natural functions, leading to negative environmental impacts.

Preserving mangroves from the ground up

Given the importance of mangroves for numerous ecosystem services that range from coastal protection, biodiversity conservation, carbon sequestration, food sources, and sociocultural significance, Indonesia holds a leading role in keeping mangrove ecosystems within a steady state.

It is crucial for us, both as individuals and as part of our communities, to take bold and decisive actions to safeguard and restore these vital coastal guardians.

Be curious about our seafood

Becoming more informed consumers goes a long way for mangrove conservation because many degraded mangrove areas result from unsustainable shrimp farming practices.

By increasing our preferences for sustainable seafood, we take part in creating healthy competition among seafood industries and enhancing more sustainable and responsible market ecosystems for other consumers who are equally interested in mangrove conservation and environmental stewardship.

While certifications like MSC (Marine Stewardship Council) or ASC (Aquaculture Stewardship Council) are common identifiers to sustainable seafood, choosing locally sourced seafood that promotes sustainable practices and empowers local fisheries (eg, from a company like Aruna) also contributes to reducing mangrove deforestation and promoting the health of coastal ecosystems.

Reforest our mangroves with local communities

Mangroves are highly effective carbon sinks, capturing up to four times more carbon dioxide per hectare than terrestrial forests. Due to the massive loss of mangrove forests, restoring these ecosystems is crucial not only for mitigating climate change but also for supporting local livelihoods. Even more, mangrove reforestation, particularly in areas previously used for aquaculture, enhances blue carbon sequestration and helps reverse environmental damage.

Indonesia has made some efforts toward mangrove reforestation through the establishment of the community-based mangrove management (CBMM) program. This program aims to restore a staggering 600,000 hectares of degraded mangrove ecosystems by 2024 through the active participation of mangrove local communities. It fosters collaborative decision-making, strengthens a sense of capacity, ownership, and responsibility among key stakeholders, and appreciates knowledge sharing from those most impacted by any changes in the system. Integrating this knowledge strengthens programs’ long-term sustainability and effectiveness.

A case study from Central Java exemplifies the effectiveness of a well-designed CBMM program. This project incorporated long-term funding mechanisms, enhanced acceptance of protective legislation, and broader public support. Furthermore, it employed a wider variety of mangrove species for reforestation and implemented measures to mitigate wave action in highly eroded areas, thereby supporting a higher diversity of macrofauna.

Explore mangrove-based ecotourism

Ecotourism offers another fun approach to mangrove conservation.

A program in Bukit Batu, Riau, for example, was designed to not only avoid mangrove degradation but also capitalize on the historical significance of the naval base of the ancient Siak Kingdom. Integrating tourism into mangrove conservation provides incentives for communities to become more invested in conservation practices, all the while deepening tourists’ appreciation for the environment.

However, such an approach should carefully consider the unintended consequences that often come along with tourism, such as social inequalities and more waste. For example, an increasing amount of waste will necessitate the development of adequate waste management infrastructure to prevent marine pollution. It is therefore crucial to ensure that the benefits of ecotourism outweigh the costs of any plausible consequences.

Safeguarding and restoring mangrove ecosystems is imperative for environmental sustainability and the well-being of local communities. By taking small steps toward mangrove conservation, we can inspire others to follow suit, gradually create transformative results, and help shape the future of our mighty mangroves.

References:

Primavera, J.H. et al. (2019) ‘The mangrove ecosystem’, World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation, pp. 1–34. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-805052-1.00001-2.

Middleton, L. et al. (2024) ‘“we don’t need to worry because we will find food tomorrow”: Local knowledge and drivers of mangroves as a food system through a gendered lens in West Kalimantan, Indonesia’, Sustainability, 16(8), p. 3229. doi:10.3390/su16083229.

Kibria, G. (2013) Mangrove forests- its role in livelihoods, carbon sinks and disaster mitigation . Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261178318_Mangrove_Forests-_Its_Role_in_Livelihoods_Carbon_Sinks_and_Disaster_Mitigation (Accessed: 01 August 2024).

Salampessy, M.L. et al. (2015) ‘Cultural Capital of the communities in the mangrove conservation in the coastal areas of Ambon Dalam Bay, Moluccas, Indonesia’, Procedia Environmental Sciences, 23, pp. 222–229. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2015.01.034.

Ickowitz, A. et al. (2023) ‘Quantifying the contribution of mangroves to local fish consumption in Indonesia: A cross-sectional spatial analysis’, The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(10). doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(23)00196-1.

Galuh Sekar A. (2022) Mengenal Hutan Perempuan di Papua, Forestation FKT UGM | Family of Forest Resource Conservation. Available at: https://forestation.fkt.ugm.ac.id/2022/11/13/mengenal-hutan-perempuan-di-papua/ (Accessed: 01 August 2024).

Arifanti, V.B. et al. (2021) ‘Mangrove deforestation and CO2 emissions in Indonesia’, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 874(1), p. 012006. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/874/1/012006.

Taneja, G. and Buisson, M.C. (2023) ‘Exploring the role of mangroves in mitigating food system emissions: bridging global experiences and local action’ Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). CGIAR Initiative on Low-Emission Food Systems. 30p.

Mitra, A. (2019) ‘Ecosystem Services of mangroves: An overview’, Mangrove Forests in India, pp. 1–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-20595-9_1.

Indonesia Sustainable Landscapes Management Program (SLMP) (no date) World Bank. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/indonesia-sustainable-landscapes-management-program/practice (Accessed: 01 August 2024).

Arifanti, V.B. et al. (2022) ‘Challenges and strategies for Sustainable Mangrove Management in Indonesia: A Review’, Forests, 13(5), p. 695. doi:10.3390/f13050695.

Damastuti, E. et al. (2022) ‘Effectiveness of community-based mangrove management for Biodiversity Conservation: A case study from central java, Indonesia’, Trees, Forests and People, 7, p. 100202. doi:10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100202.

Nawari, Syahza, A. and Siregar, Y.I. (2021) ‘Community-based mangrove forest management as ecosystem services provider for reducing CO2 Emissions with Carbon Credit system in Bengkalis District, Riau, Indonesia’, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2049(1), p. 012074. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2049/1/012074.

Abhishyant Kidangoor, S.W. et al. (2011) Vanishing mangroves are carbon sequestration powerhouses, Mongabay Environmental News. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2011/04/vanishing-mangroves-are-carbon-sequestration-powerhouses/ (Accessed: 02 August 2024).

K, M., Arumugam, T. and Prakash, A. (2024) ‘A comparative study on carbon sequestration potential of disturbed and undisturbed mangrove ecosystems in Kannur district, Kerala, South India’, Results in Engineering, 21, p. 101716. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101716.

US Department of Commerce, N.O. and A.A. (2013) What is blue carbon?, NOAA’s National Ocean Service. Available at: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/bluecarbon.html (Accessed: 02 August 2024).